Seventy five years ago today tens of thousands of military personnel were patiently poised in East Sussex and along the south coast, waiting for the order to embark. Following months of intricate planning only one thing was holding up the massive offensive to begin the liberation of mainland Europe. D-day was being delayed by the weather.

Soldiers were camped at Firle Place, Stanmer Park, Ditchling, Plumpton, Seaford, Lewes and Eastbourne. Tanks were concealed in nearby woodland and residents were reminded to keep quiet about all the activity.

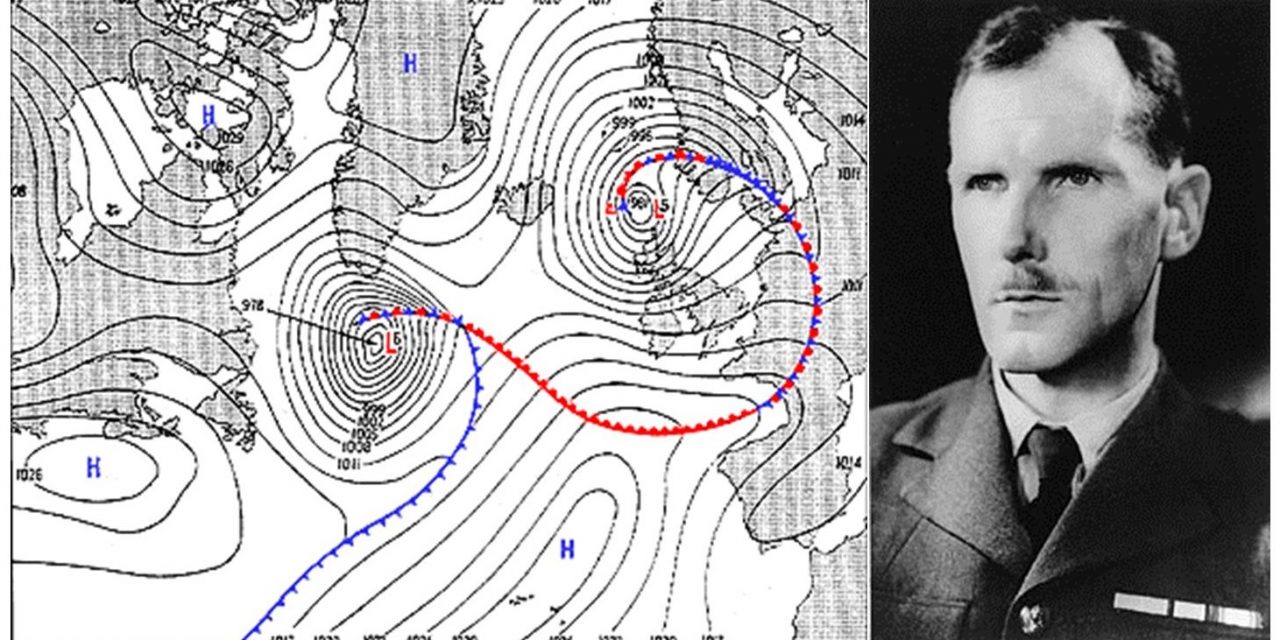

But bad weather, frustratingly, meant conditions in the channel threatened the whole operation which was to become the largest seaborne invasion in history. It was then that a meteorologist whose final home was in Seaford, made arguably the most important weather forecast in history.

Agonising delay

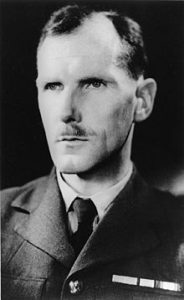

Group Captain James M Stagg, chief meteorological officer for Operation Overlord, the code name for the offensive, met with General Eisenhower on the evening of 4 June 1944. Eisenhower had planned for the invasion to commence on 5 June, but the bad weather forced an agonising delay.

Without the modern technology that provides more accurate weather forecasts, Stagg and his meteorological team pored over the weather reports and spotted a potential break in the storm. He told Eisenhower there would be a small window in the weather early on 6 June to allow the invasion to go ahead. Eisenhower now had a choice – trust Stagg’s weather forecast or postpone further.

The Germans were taking a different reading of the weather. They believed in such stormy conditions no invasion would be possible for several days. Some of the defending troops were sent off for military exercises and many senior officers were enjoying a long weekend. Even Field Marshal Erwin Rommel went back home to Germany to celebrate his wife’s birthday.

A difficult choice

But for Eisenhower to delay further would mean a massive stand down of the invasion force for at least a couple of weeks as the phase of the moon, the tides, and the time of day meant only a few days each month were deemed suitable for an invasion. The Allied Commander took the risk, listened to Stagg’s advice, and the invasion began on 6 June 1944.

Eyewitness accounts of the day describe a ‘strange silence’ in East Sussex and right along the south coast after the troops departed by sea and air for Normandy.

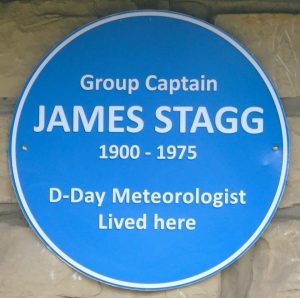

Following D-Day Stagg was appointed as an Officer of the US Legion, before being elected as President of the Royal Meteorological Society. He was knighted in 1954. Stagg retired in 1960 and died in Seaford in 1975. A plaque marks the house in Carlton Road where he lived.

Following his accurate weather forecast, more than 7,000 vessels successfully landed more than 170,000 Allied troops in France, many having left from the Sussex coast. The window in the weather, accurately predicted by Stagg, gave them just enough time to land a sufficient force to begin the liberation invasion.