When Alan Turing’s image adorns the new £50 note in 2021 it will be a fitting tribute to one of the greatest minds of the 20th Century – a mind that owes at least part of its genius to East Sussex.

For Turing, the second world war code-breaker and acknowledged as the father of modern computing, spent most of his early childhood years at school and home in Hastings, St Leonards and Frant, near Crowborough.

Blue plaque

During his childhood Turing’s parents travelled between Hastings and India, leaving their two sons to stay with a retired Army couple. In Hastings, Turing stayed at Baston Lodge, Upper Maze Hill, St Leonards-on-Sea, now marked with a blue plaque. That plaque was unveiled on 23 June 2012, the centenary of his birth.

Alan Turing, age 16

Turing’s parents enrolled him at St Michael’s, a day school in 20 Charles Road, St Leonards-on-Sea, at the age of six. The headmistress recognised his talent early on, as did many of his subsequent teachers. Then between January 1922 and 1926 he was educated at Hazelhurst Preparatory School, an independent school in Frant.

These were the educational foundations of a man whose genius and vision would play a pivotal role not only in securing victory in the second world war, but also in shaping the computerised world in which we now live.

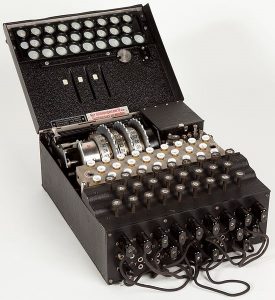

Enigma

Turing is probably most famous for his work as a second world war codebreaker at Bletchley Park. His part in breaking the German enigma code is credited with being key in changing the allies’ fortunes in the Battle of the Atlantic and the wider second world war.

The enigma machine used by the German military to send encrypted messages. The code was broken by Turing.

But after the war, he became a leading light in the development of computers and computing theory. He created the Automated Computing Engine which was basically the model of a general-purpose computer, and he is also widely considered to be the father of artificial intelligence by considering the question of whether machines could think.

Prosecution

But despite these accomplishments, Turing was never properly recognised during his lifetime, due to his homosexuality, which was then a crime. Instead of being hailed a national hero, tragically he was prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts. He accepted chemical castration treatment as an alternative to prison.

Turing died in 1954, 16 days before his 42nd birthday, from cyanide poisoning. An inquest concluded his death was suicide.

Looking back from a 21st Century perspective this series of events seems unbelievable and shameful. It was not only a huge slap in the face for a man whose genius shortened the war and potentially saved thousands of lives, but it also robbed us of a mind which would have gone on to contribute even more to the development of the digital world.

Apology and pardon

In 2009, following an Internet campaign, the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official public apology on behalf of the British government for “the appalling way he was treated”. The Queen granted Turing a posthumous pardon in 2013.

The £50 note might not be the most frequent piece of UK currency to visit our wallets and purses, but it’s nonetheless an appropriate tribute to a man to whom we owe so very much.