As the First World War raged across Europe, the first Black recruits from the West Indies arrived in Seaford. Often travelling at their own expense to enlist, they journeyed to join the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR),

The regiment was a separate Black unit within the British Army. The first recruits arrived from Jamaica in 1915 to train at the camp near the small East Sussex town. While each person was prepared to fight the German forces and die for our freedom and liberty – they also had to battle racism and discrimination from within the British Army.

Here we mark Black History Month by exploring the story of those men who arrived in Sussex as volunteers, fought as soldiers, and at the end of the war were still fighting for fair wages.

Black History Month

The theme of this year’s Black History Month is ‘Reclaiming Narratives’.

The month provides a vital opportunity to recognise and correct narratives of Black history and culture, showcase untold success stories and the full complexity of Black heritage.

This theme is not just about revisiting history, it’s about taking ownership of the stories that define Black culture and which have the potential to inspire and educate the next generation of Black people in East Sussex.

World War I Begins

After Britain joined the First World War in 1914, Black Britons were recruited in all branches of the armed forces. Later, soldiers from Nigeria, Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, Gambia, and other African colonies were recruited for important African campaigns.

During the war

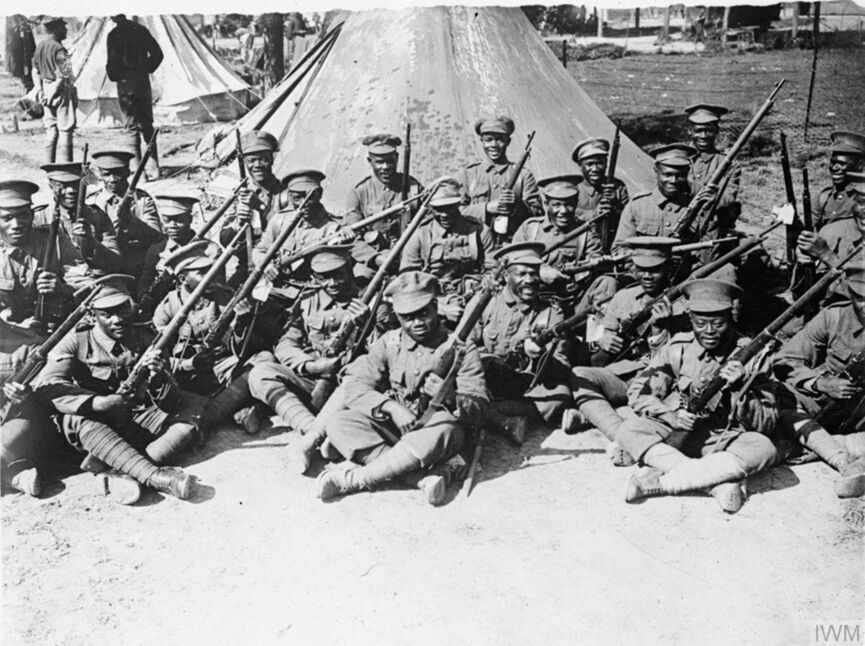

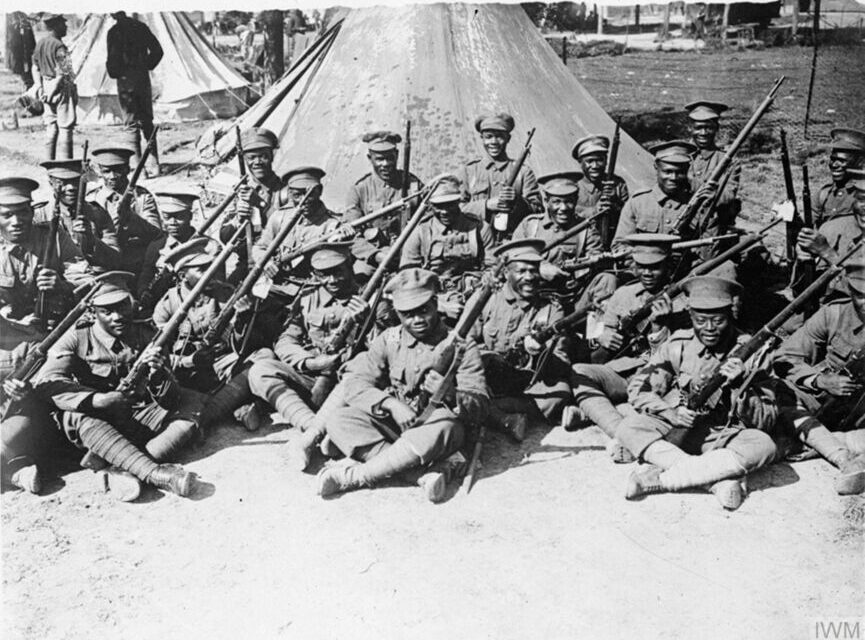

Troops of the West Indies Regiment in camp on the Albert – Amiens road in France, September 1916.

The Black BWIR soldiers were mostly led by white officers and used initially as non-combatant soldiers. Though they resented it, they were only given labouring work. This includes carrying ammunition, laying telephone wires, and digging trenches. This work was dangerous and often carried out within range of German artillery and snipers.

After the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the shortage of manpower on the Western Front meant the BWIR was needed to take a more active combat role. Even so, they were only permitted to fight outside Europe, for example in Palestine and Jordan.

The end of the war

By the end of the war in November 1918, a total of 15,204 Black men had served in the BWIR. The Regiment had lost 185 soldiers in action. A further 1,071 died of illness and 697 were wounded.

In total BWIR soldiers were awarded 81 medals and mentioned 49 times in military despatches, a clear sign of their vital contribution. The former Jamaican Prime Minister Norman Manley, a member of the BWIR, received the Military Medal for gallantry.

But throughout the war, West Indian troops had to deal with racism from their fellow soldiers and the military authorities. In 1918 they were denied a pay rise given to other British troops on the basis they had been classified as ‘natives’. The increase was eventually granted following protests by serving soldiers and islands of the commonwealth.

After a campaign in Palestine, the BWIR commanding officer wrote: “Outside my own division there are no troops I would sooner have with me than the BWIs who have won the highest opinions of all who have been with them during our operations here”.

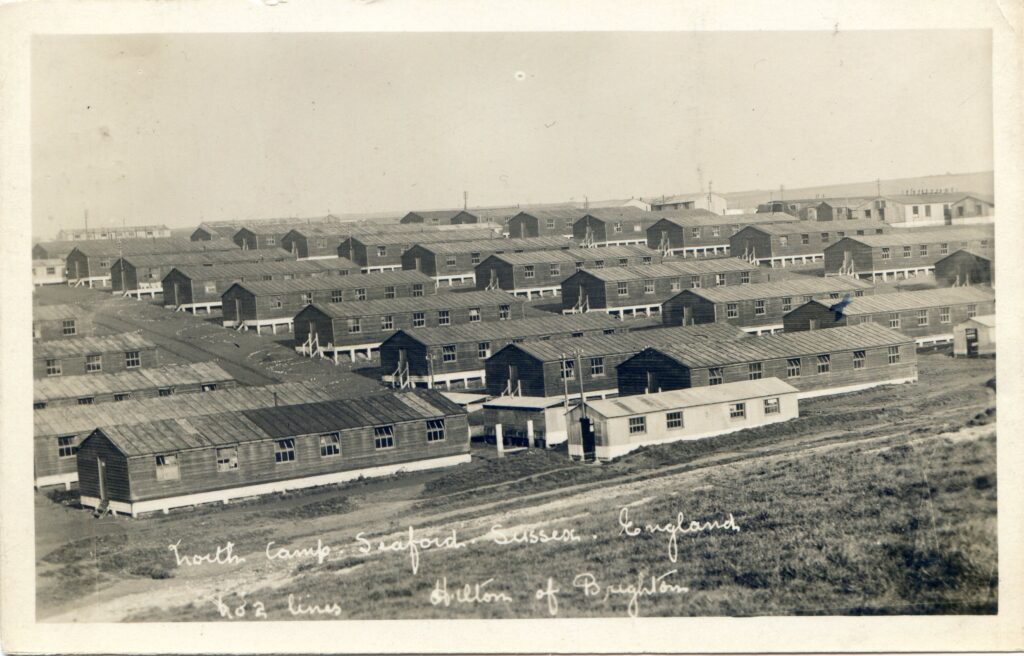

North Camp Seaford, 26 Apr 1919. Photo courtesy of the Seaford Museum and Heritage Society

The camp in Seaford

Crest of the British West Indies Regiment

Seaford camp is now only remembered by North Camp Lane. But during the war it was spread over a vast area of Seaford Head, South Hill and the Cuckmere Valley. North Camp covered farmland near East Blatchington and now lies entirely underneath the modern town.

There are almost 300 Commonwealth War Graves in Seaford Cemetery, and 19 of the headstones display the BWIR crest.

Learn lots more about the BWIR at our free pop-up museum in Lewes, Hut Stories, on October 26th-27th, see here: https://fb.me/e/48WNe5AKh

Spend time in the building once used as their camp church!

You can also read about the event on the Visit Lewes website: https://www.visitlewes.co.uk/whats-on/hut-stories