How is it that something which happened almost 1,000 years ago seems only to grow in our imagination as time rolls forward?

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October (you know which year) and as the anniversary approaches there’s usually a flurry of questions and new theories about exactly what happened when the armies of Harold Godwinson and William of Normandy clashed on Sussex soil.

Part of our fascination with the battle is explained by its importance, deciding who ruled England and changing the destiny of a nation.

And partly we’re intrigued because there are so many different accounts of the battle (not surprising perhaps given the 955-year gap). There are some written records of the battle from near the time: including the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; and an account of the deeds of William compiled by a Norman admirer a few years later.

And of course there’s the Bayeux tapestry, produced by the Normans to record their victory and conquest of England.

But those sources don’t agree on what happened at the battle and later works only complicate the picture. The result is there are many things we don’t know for sure about England’s most famous battle and which still make for fascinating speculation.

Where exactly was the battle?

The most widely accepted answer is of course at Battle, the town named for the historic clash.

William vowed to build and dedicate a church at the site of his victory over the Saxons and this building, Battle Abbey, is assumed to mark the centre of the action.

Harold drew up his troops on the ridge where the abbey remains now stand, forcing the Norman army to attack uphill from the lower marshy ground they occupied after landing at Pevensey and marching in from Hastings.

Battle Abbey, now maintained by English Heritage, is certainly the place to start a tour of all things 1066. For the 2021 anniversary weekend (Saturday October 9 and Sunday October 10) you can buy tickets to a re-enactment of the battle with 600 armoured and tooled-up warriors re-creating the conflict. Almost all year round though the remains of the abbey, the battlefield and its history are open to visitors through exhibitions, audio tours and more. More details from English Heritage.

There are though, still competing theories about where the clash took place with some arguing for Caldbec Hill on the other side of town and some for Crowhurst – a couple of miles to the south.

Read the Anglo-Saxon chronicle and it tells you only that Harold, after a long march from a separate battle in Yorkshire, rallied his troops ‘at the grey apple-tree’, thought to be on the track from Hastings to London.

“Then King William came from Normandy into Pevensey, on the eve of the Feast of St. Michael, and as soon as they were fit, made a castle at Hastings market-town. Then this became known to King Harold and he gathered a great raiding-army, and came against him at the grey apple-tree.”

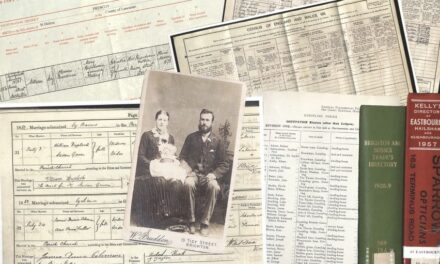

Re-enactors mark the anniversary of the Battle of Hastings (pic English Heritage)

How many troops were involved?

Historians now tend to think there were about 7,000 soldiers on each side – large armies for the time. But some Norman accounts claim William, believing he was the rightful King of England, brought as many as 60,000 men with him in his invasion force and there are those who think he could have fielded 10,000 or more in the battle.

Harold’s Saxon army was made up of some archers but mostly infantry, men who rode to the battlefield and then dismounted to fight with shields and axes. This was the force which lined up its shield wall along the ridge to defy the Norman advance.

William’s army, by contrast, included cavalry as well as archers and infantry. It was these mounted knights who finally won an all-day battle, surrounding and cutting off Harold’s foot-soldiers after they broke up their shield wall in pursuit of the enemy and triggered their doom.

As the chronicle puts it:

“There King Harold was killed and Earl Leofwine his brother, and Earl Gyrth his brother, and many good men; and the French remained masters of the field, even as God granted it to them because of the sins of the people … and always after that it grew much worse. May the end be good when God wills!”

How exactly did Harold die?

Generations of schoolchildren grew up learning the King of England was killed by an arrow in the eye – a scene captured in the Bayeux tapestry. Simon Schama, in his History of Britain, is convinced too, saying: ‘The tapestry leaves no room for ambiguity.’

Not so, argues Anglo-Saxon historian Alison Hudson, you can decode the tapestry as suggesting several possible fates for Harold:

‘Was he killed by an arrow to the eye, as claimed by Amatus of Monte Cassino, writing in the 11th century? Was he hacked to bits, as recounted by Bishop Guy of Amiens (died 1075)? Or was he shot with arrows and then put to the sword, as described by the 12th-century chronicler, Henry of Huntingdon?’

Whichever account you prefer however, it’s clear that Harold was one of thousands who died on the field known as Senlac. Except….

….one tale written over 200 years later claimed that Harold survived the battle, was treated in secret of his wounds before fleeing overseas and then returning to England to live out his days as a hermit living in a cave.

It’s almost certainly folklore rather than history but it’s a perfect example of how a 1,000-year-old story, especially on its anniversary, can grip us from across the centuries.

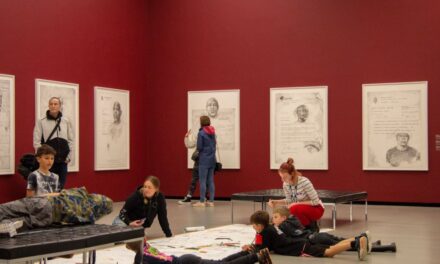

Archers let fly at the battle (pic English Heritage)

To find out more why not?

Read about the battle and the Norman conquest via your local library or the elibrary? https://www.eastsussex.gov.uk/libraries/locations/

Online library services | East Sussex County Council

Visit Battle and its famous abbey https://www.visit1066country.com/destinations/battle